Lyuba Galkina is a Trustee of Gift of Life. She is a co-founder of the ZIMA group, and a marketer who has previously worked for Pepsi, Nike, Apple, and Google. Her career, indeed her entire life, is proof that drive and hard work trump everything, and can help you go beyond your roots in a tiny provincial town in Tajikistan to success on an international scale. But Lyuba tells us that success is ephemeral, and that it’s not a word she’d apply to herself.

You’ve worked for Pepsi in Russia, then in senior management for Nike in Holland, as well as in consulting for Sesame Workshop and Apple, not to mention your work with Google, the British Fashion Council, and Vivienne Westwood. These days, you make your home in London. That’s a mindboggling career for someone born in a Soviet village in Bryansk Oblast. How on earth did you manage it?

It’s true that I was born in a little village in the middle of nowhere, and grew up in Leninabad in the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic. Today, there’s no such town—in fact, no such country. My parents divorced when I was seven, and my mother had to work three jobs in order to look after me: she was a librarian by day, a janitor at the same library in the evening, and then a letter sorter at a post office the very same night. Despite all this, she made sure I always looked good, taking the time to sew and knit for me. It was the pinnacle of her dreams for me to become a music teacher. She was convinced that this was the peak of what a woman could achieve in life. But at 16, I went to Moscow despite her objections, and began my studies at the very prestigious economics faculty of Moscow State University. It was no less unreal than landing on the Moon.

Lyuba Galkina at the Gala, 2018

At the faculty, they called me “the Eastern star”, because they found it funny to see this tall blonde… from Tajikistan. I was fortunate to not only finish with a top-tier degree, but to be accepted for doctoral study, become a doctor of economic sciences, and even obtain my own position at the faculty. It was something I couldn’t have dreamed of in my student days.

But right at the point where I got my new job, perestroika arrived, and all my accomplishments were of no use to anyone. There was too much going on for anyone to care about Marx’s Capital or the works of Lenin.

It was a very dynamic time, and that was when I got another stroke of luck—I was invited to work at a little company called the Crocus Group. Back then, it occupied a former greengrocer’s—barely more than a tent—next to the Belyaevo metro station, and its founder Araz Agalarov, now one of the richest people in Russia, was only just beginning to build his empire. It was his idea to start presenting international trade exhibitions in Russia, and he invited a few people from Moscow State University in order to make it happen, for which I’m forever grateful. And that’s how I started my career in marketing without even knowing the word.

Could you tell us about your work for Pepsi?

Those were the early days of PR and marketing in Russia, and I had to learn everything on the job. Our boldest project had to be when we came up with the idea of launching a Pepsi can with the new logo into space and recording it as a video clip.

Pepsi Blue Launch at the hangar of the Gatwick airport in front of the Concorde painted Blue with the group of journalists from Russia

Astronauts were stepping into outer space holding the can, while we were sitting in the Flight Control Centre and directing them from Earth. Since it was 1996 and the economy was in ruins, the whole thing cost a pittance. But while we were filming in the Centre, I felt a deep pang of sorrow. We were bringing in crates of Pepsi, and the scientists were dividing them up and drinking them with this innocent childlike joy. It ended up being a project at odds with itself, happy and sad at the same time. Even now, I’m very sensitive to everything that happens in Russia, even though I haven’t lived there for 18 years.

At the Space center with Inflatable Pepsi can which was sent to Space

How did you end up in Holland?

In 1998, I got a call from an international recruitment company. At that point, I’d only just given birth to my daughter and was working for Pepsi part-time, but I was considering giving it up and going back to teach at a university. That thought has never left me, incidentally. The recruiters invited me for an interview at “a certain sports company”.

Back then, Nike had only just established its European headquarters, in Holland, and was considering opening a branch in Russia. I was hired on what were, for that time, utterly incredible terms. Then, a year, later, they told me they needed me in Holland.

I was sure my husband would never go for it—he already had his own PC company which he’d built from the ground up. But he said he was willing to give it a go. That was how in early January 2000, our entire family found ourselves at Schiphol Airport in Holland. I’ve never heard of anyone from Russia who would have been prepared, in those days, to travel abroad to take up that kind of role. I was the only woman and the only Russian among the company’s top management.

Pictured for Cosmopolitan Russia by Vlad Loktev

Were you scared?

No. But, the company being what it was, and competition with my male colleagues being as fierce as it was, I had to constantly think outside the box. Let me tell you a story from my Nike days.

I was the regional director for Central and Eastern Europe, the Near East and Africa. One day, at during a conference at the Nike global HQ, I had to describe retail development within that (not exactly small) region. I opened my presentation by telling them about how back in the distant Soviet days, when we were “building communism”, many dreamed of having their own pair of Nike trainers.

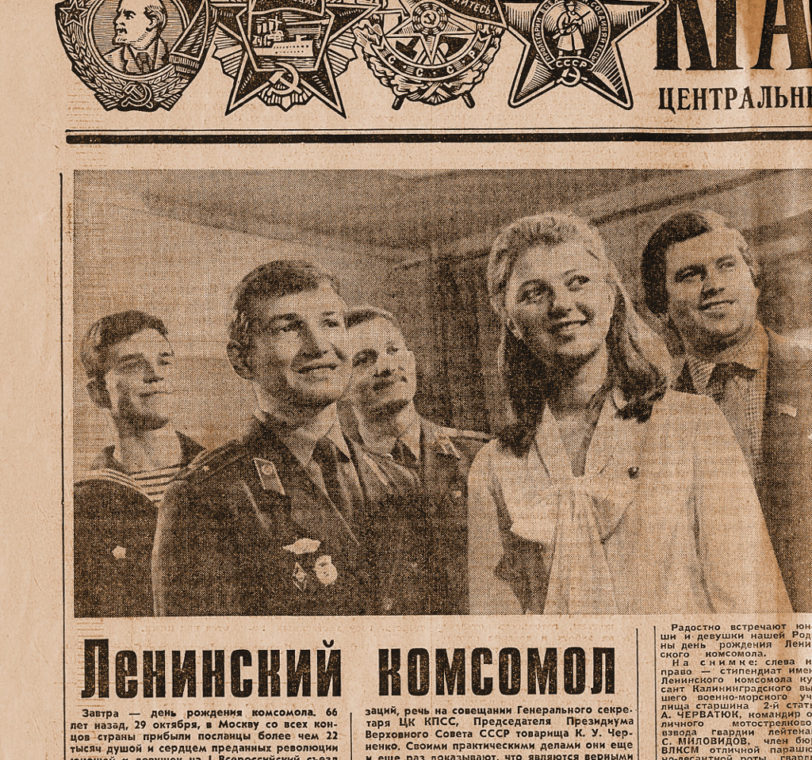

Pictured in the Soviet Army newspaper “Red Star”, 1985

My presentation was named “Dreams come true”, and I opened with a photo from the front page of a 1985 issue of the Krasnaya Zvezda newspaper, titled “The best student, the best soldier, and the best worker”. It had me, a top student and Komsomol member, in the centre, with a soldier, a sailor, and a worker standing next to me. After giving them those opening words about Nike trainers, I presented the numbers, together with photos of attractive shops. Then, as my closing image, I used a photo of a bare-footed African boy standing on the seashore: “But somewhere out there, there are those who are still dreaming…” Africa was our new region, the next to be shod in Nike sneakers.

When the audience realised that I was the girl in the photo, of course their minds were blown. I’ll admit that back in my student days, I was terribly embarrassed at having my friends see that shot, and even thought about buying up the whole lot so nobody could ever see it again. But in the end, I managed to find a good use for it.

You used to have such bold, wide-scale projects. Now you’re organising charity balls. Where’s the excitement?

Charity work is more exciting than anything in the world. From the outside, Gift of Life’s London charity balls look like they’re just lavish, glamorous events. But behind the curtain, everything is much more complicated.

A charity ball is a huge, complex project where a great number of people are counting on you. Sometimes, you’re in a frenzy as you rush around organising everything, gathering auction lots, inviting performers—and all while some helpful lady is phoning you every minute because it’s vital that she be seated next to a man at least 180 cm tall, with blond hair, brown eyes, and a job in banking. And it doesn’t matter that there are another 250 guests. You have to please everyone.

With Chulpan Khamatova and Ralph Fiennes at the Gala, 2019

In order to put together a ball or organise some other charity event, I have to leverage all the experience I built up working with Nike, Pepsi and the other companies. Marketing is marketing, no matter whether it’s commercial or charity. The better a professional you are, the more money you make. But there’s a difference between boosting trainer sales and paying for medicines and doctors to help sick children. How much you accomplish matters on a whole other level.

During one of our charity evenings, Stephen Fry introduced Rita Khairullina, a pretty girl in a ball gown, with a lovely haircut. But only two years ago, she’d been lying in a hospital bed with no hair at all, and her parents were desperately looking for money with which to buy her medicine. Back then, it was our charity ball guests who helped her.

With Stephen Fry, Ingeborga Dapkunaite and Vladimir Pozner at the Gala, 2015

In 2018, Viliam Khailo, a student at the Gnesin Music Academy, played for us alongside the violin virtuoso Vladimir Spivakov. It wasn’t that long ago that the charity helped bring Viliam back from the very brink. Just thinking about it makes shivers run down my spine. This isn’t a paying job, and I don’t get weekends off, but I can’t imagine anything more rewarding.

Of course, it’s not all me. I’m surrounded by a small but wonderful circle of like-minded people. It takes humongous effort to organise a charity ball, but in the morning, when you find out that you’ve raised, say, £500,000, and you know exactly where that money’s going… there’s nothing like it.

Podari Zhizn works in Moscow, while Gift of Life works in London. How does the charity culture differ between these two countries?

Back when I’d just started, the difference was massive. In Europe, you’re immersed in charity culture from childhood. In Holland and in England, my daughter and I got into all sorts of charity activities, from baking cakes to support a class in an African school, to collecting food for the homeless every year. Donating at least two to three pounds to charity, if not more, is a standard part of life, so normal that no one even talks about it.

I’m glad that charity is becoming an important part of life in Russia as well. It feels great that it’s our Podari Zhizn that’s getting thousands of people to help ill children, paving the way for other Russian charities to follow.

With Ksenia Rappoport and Alexander Khan at the Gift of Life evening, 2019

Within the Russian-speaking community, there are many successful women who got to where they are through their own hard work, but who fear the word “feminist”, and avoid identifying themselves with the feminist movement. How do you feel about the feminist agenda?

You know, back at Nike, we were often invited to various seminars where they talked about how hard it is to be a woman in the modern world. But if I’m honest, somehow or other, it was smooth sailing for me. I didn’t have to fight for my place in the sun just because I’m a woman. People kept promoting me, paying me salaries, giving me shares…

I’ve also always cared a great deal about looking good, and being a good daughter, wife and mother. All this was my personal choice, which is something everyone has.

What does “success” mean to you?

To me, success is an ephemeral concept. I’ve always achieved what I put my mind to, but I don’t feel successful.

I always have something to pursue. I always feel like there’s another missing ingredient to look for. I want to keep making things even better, and it massively gets on people’s nerves. I’ve never felt like resting on my laurels. If something’s turned out well, I instantly want to keep going even further!

Based on the interview with Lyuba Galkina in Zima Magazine.

Photos kindly provided by Lyuba Galkina and the Gift of Life photo service.

We can help more children beat cancer together! Please, visit our Donate page to support.